Strace Spelunking: Diving Deep into SSH Password Discovery

Overview

In the cloud landscape, there are multitude of services and offerings that attackers can abuse to gain unauthorized access to an organizations cloud environment. In most cases we’ll see threat actors find hardcoded cloud credentials in a git repository or abuse a known SSRF vulnerability to obtain temporary cloud credentials.

In an enterprise environment is not unusual to see isolated EC2 instances that are not domain joined. These EC2 instances can be used for testing, development or really anything that creator wanted. These isolated EC2 instances may seem like celestial bodies, distant and impervious to typical security threats (i.e no customer PII is stored on these servers), however beneath this isolation, exists a true concern. With a combination of strace subtletites and the overall inherent complexites of SSH, lateral expansion within these standalone instances isn’t just feasible, it is alarmingly straightforward. In this blog post we will delve into the art of unravelling SSH passwords and unveil the eerie eas of lateral movement in non domain joined EC2 environments to servers within an Active Directory environment.

Disclaimer: This is not a novel technique. The idea of using strace to retrieve cleartext credentials is nothing inherently new. With that said, documentation regarding this attack vector is extremely limited and this post is to serve as educational material for red teamers, blue teamers and any security analyst helping to secure their organizations network.

I came across two places on the internet that spoke about this very attack and have aimed to make it better and add more context to it. Those links can be found here:

Sniffing SSH Passwords | The Network Logician

Spying on ssh password using strace | by debojit | Medium

I have also created a script on Github that can easily be deployed for red teamers. I would adjust the script to fit your needs and review the code before running to maintain better OPSEC.

As always you must have permission to use strace in this regard.

TLDR:

Pull cleartext credentials from SSH with the use of strace.

The Curious Case of Mr.Strace in the Linux Machine

Before we can paint the picture of an actual use case of this, we should first define and understand what strace is and isn’t.

Strace (strace) is a diagnostic, debugging, and instructional utility for Linux and other Unix-like operating systems. It provides a mechanism to trace system calls and signals executed by a specified program, or to monitor system calls made in real-time for running processes.

<aside> 💡 System Calls: When user-level applications need to request some service from the operating system such as reading a file, sending data over a network, or allocating memory—they do so by making system calls.

</aside>

Strace intercepts and records the system calls made by a process and the signals received by a process. The name "strace" essentially stands for "system call trace.” By default, strace displays a list of system calls, including their arguments, return values, and error messages (if any). This output can be instrumental in debugging and analyzing the behavior of programs.

This output can also be very difficult to digest and understand and we will work on cleaning up this data and retrieving only what is important to us.

A common use case for strace is to diagnose why a program is failing or behaving unexpectedly. By examining the list of system calls, one can often identify the exact point of failure or misbehavior.

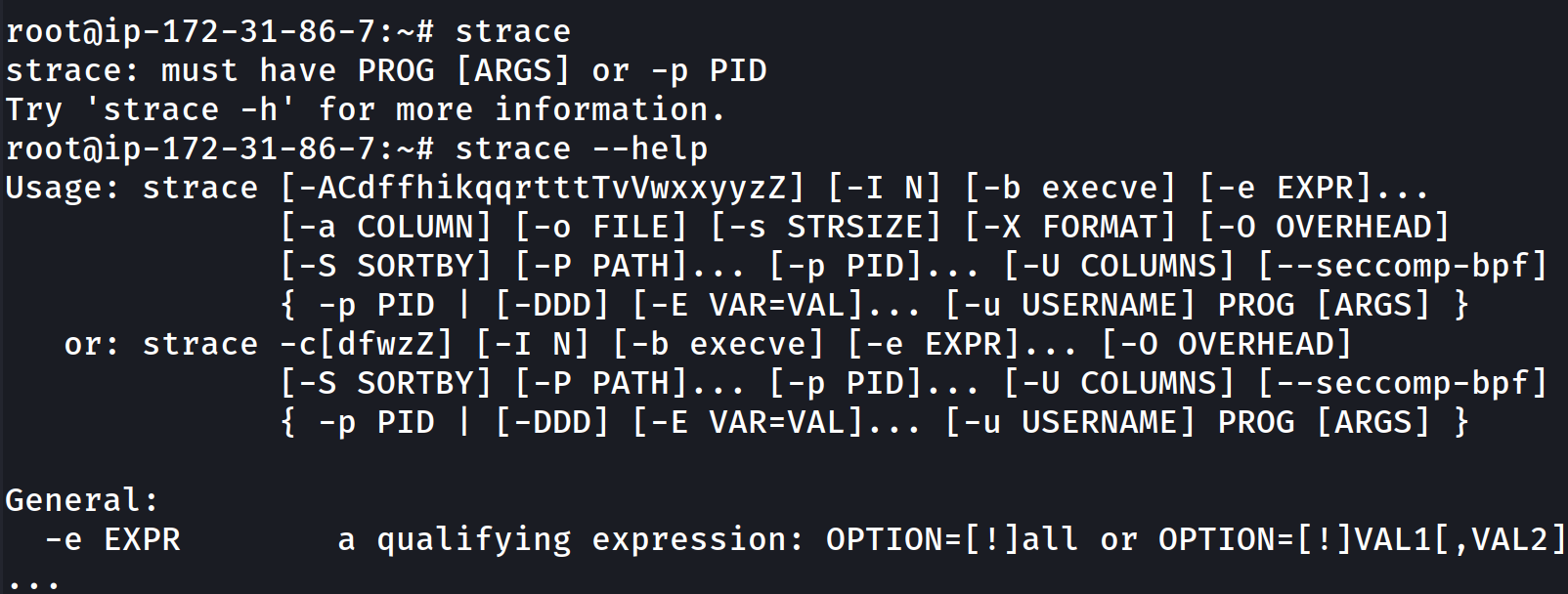

The help menu is littered with different flags and options you can use to fine tune your strace query:

So how can we use this?

If we are root on the system, we can hook the SSH process with strace and use this to uncover the plaintext password for an SSH user.

But how does this work?

There are really three main reasons why. Also keep in mind that this attack doesn’t only affect SSH but frankly any process where credentials are being entered (more on that later).

So let’s break down SSH and strace a bit more:

Initial Input: When you type your password into ssh, it's initially sent to the process in plain text. This is because your terminal just collects keystrokes and sends them to the foreground process.

The read System Call: If you use strace to trace the ssh client when you enter your password, you're likely to see the password in the output of the read system call (or a similar call) because strace is showing you the data being read from the file descriptor associated with the terminal.

Encryption: This is the big one. When an SSH client connects to a server, the password is not sent in plain text. Instead, the client and server engage in a challenge-response authentication to verify the password without directly sending the password over the network.

However, if you're using strace on the SSHD process on the server side, you may see the plaintext password if a user is connecting using password-based authentication. This is because the server needs to decrypt the challenge response to verify it against the stored (hashed) password. This does present an opportunity for those with sufficient privileges on the server to obtain plaintext passwords of users trying to authenticate.

To be clear, the password is not transmitted in plaintext over the network. But, on the server side, during the process of challenge-response verification, the plaintext password can be briefly available in memory, and this is what can be captured.

Practical Use Cases

In order to save myself the headache of spinning up an AD lab in AWS, I will just be highlighting two different EC2 servers. Server 1 is an isolated EC2 not domain joined and Server 2 is meant to be indicative of a server that is domain joined. Again it is not uncommon to see in an enterprise environment a shared root password for all Linux hosts. This in itself is bad practice and would be noted on a penetration test but it’s 2023 and these things still happen.

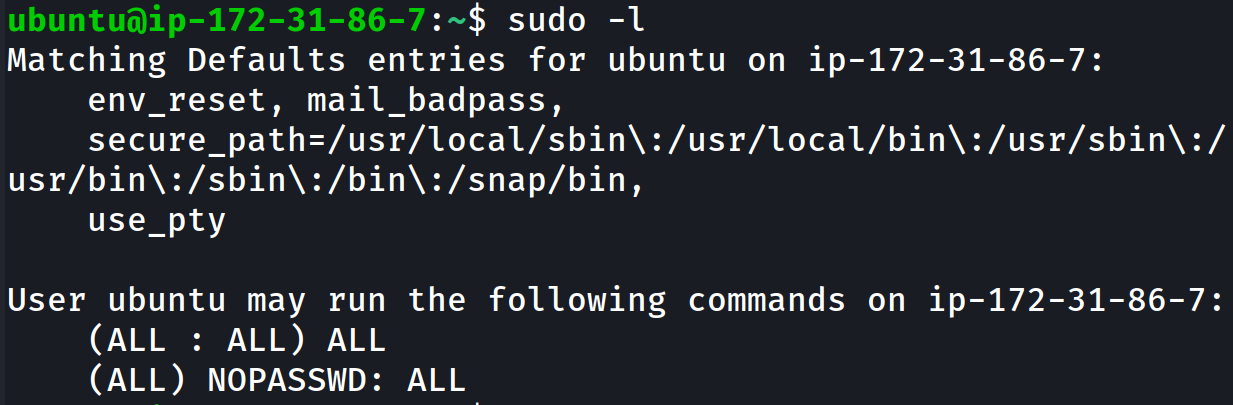

So you’ve popped root on an AWS EC2 (or frankly any other cloud or Unix like server). You realize that the ec2-user or ubuntu user has sudo all permissions

This is a default setting on many cloud providers and even virtual machines like ubuntu.

You can use a command like ps aux | grep sshd but if we circle back to the explanation of strace above, hooking an already existing ssh process won’t give us much. We need to have the process hooked when the connection is made to retrieve that password in memory once it is decrypted. So the first challenge is how can we listen for all SSH processes incoming to the server.

The first part of our command will be pgrep sshd

pgrep sshd will return the process IDs of all running sshd processes on your system. If you have multiple sshd processes running (which is possible with multiple connections or different configurations), this command will return the PIDs for each of them, one per line.

If you only want the oldest sshd process, you can use pgrep -o sshd, and for the newest, you'd use pgrep -n sshd but in the instance, as red teamers we want to grab everything.

The next part of our command xargs -I{}

The xargs utility is used to read items from standard input, delimited by blanks or newlines, and then execute a command using those items. The -I option in xargs allows you to define a placeholder that will be replaced by the input item in the command line. So to clarify:

- The

{}placeholder represents each item read byxargs. - Every occurrence of

{}in the command will be replaced by the current item being processed byxargs.

Finally the strace part strace -f -p {}

f: This option tellsstraceto follow child processes (forks) as they are created by the currently traced processes. This is useful if you want to monitor system calls of both a parent process and its children.p: This option is followed by a process ID (PID), indicating thatstraceshould attach to an already running process with that PID and start tracing its system calls (ourxargsinput)

-o ~/some/directory/strace.log

- This is where our output file will go

-v -e trace=read,write -s 128

v: This option tellsstraceto give verbose output-e trace=read: This option specifies a filter for which system calls you want to trace. In this case, you're indicating that you only want to trace thereadcalls. Any system calls other thanreadwill be ignored in the output.

-s 128

**s 64**: This specifies the maximum string size to print. For system calls that interact with strings (like read and write), strace will only print the first 64 characters of the string. If the string is longer than 64 characters, it will be truncated in the output. Adjusting the value after-slets you capture more or less of the string data, as needed.

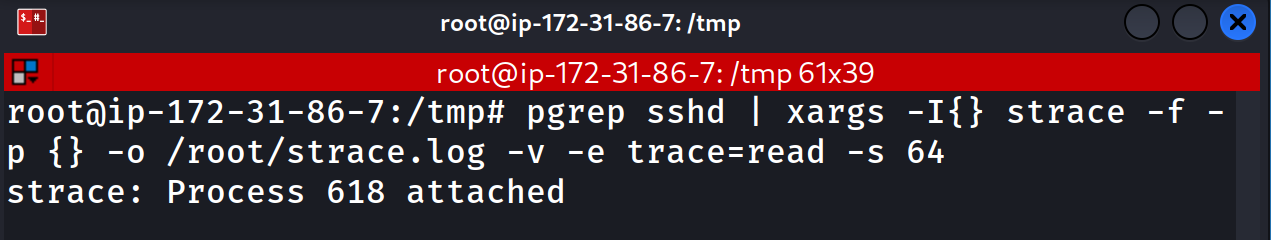

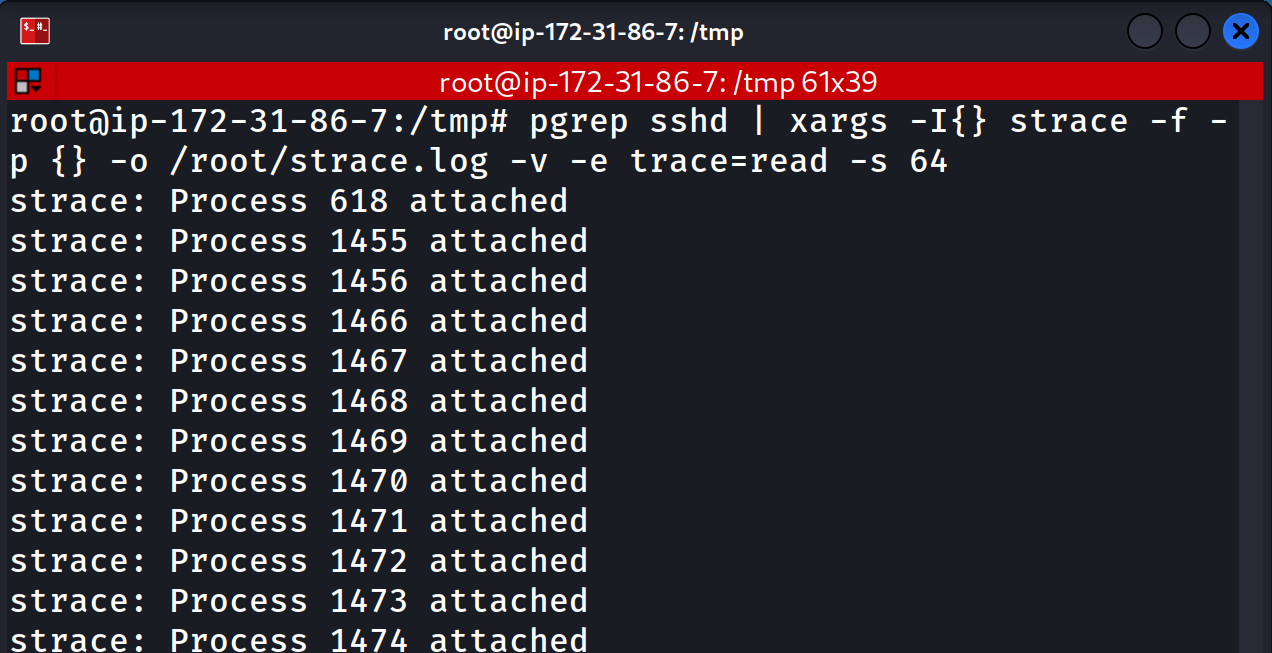

The final command is:

pgrep sshd | xargs -I{} strace -f -p {} -o ~/some/directory/debug-{}.log -v -e trace=read -s 64

But this is still far from perfect and we can see why below:

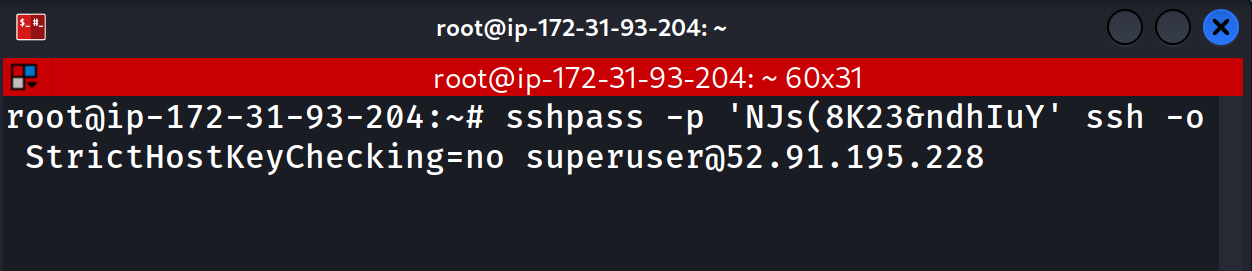

Here we are on Server 2 initiating the SSH connection:

Here we are one Server 1 having already executed our strace command:

Once the SSH connection is initiated, we can see our strace command light up as it starts to hook into any current or new SSH process:

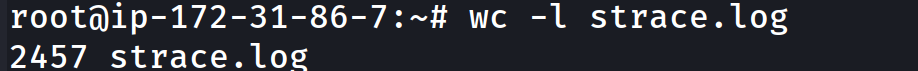

We should have a log file sitting in /root/ now, lets take a look:

Quite of a bit of lines to parse through and not to mention it’s going to be quite difficult to understand this data:

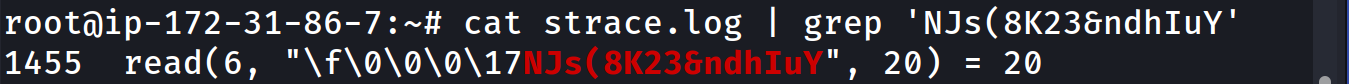

But because this is a lab environment, we can easily just grep for our password:

Excellent. We have successfully pulled a plaintext SSH password through the use of strace and SSH

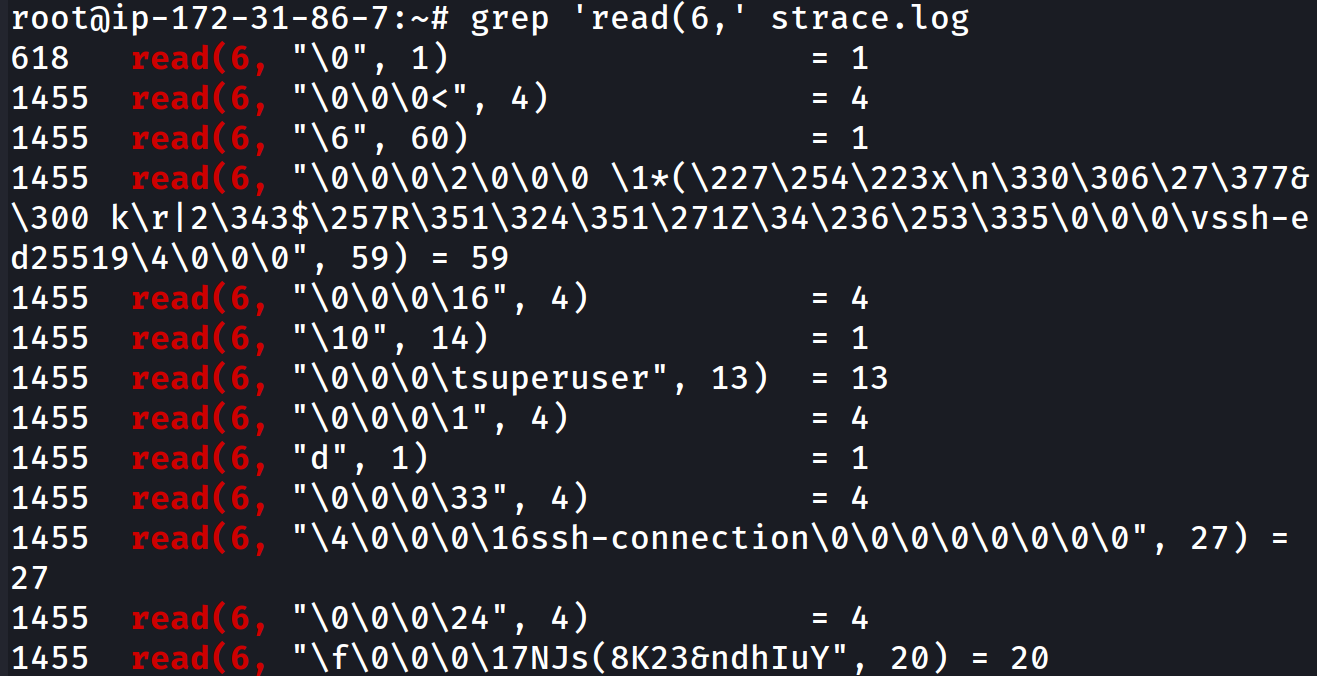

But lets break down the results further:

1455 read(6, "\\f\\0\\0\\0\\17NJs(8K23&ndhIuY", 20) = 20

1455: This is the process ID (PID) of the process that executed thereadsystem call. In this case, the process with PID1455is being traced.read: This indicates that the process executed areadsystem call. Thereadsystem call is used to read data from a file descriptor into a buffer.6: This is the file descriptor from which the process is reading. File descriptors are references to open files, sockets, or other I/O channels. In Unix-like systems, every process starts with three standard file descriptors:0(stdin),1(stdout), and2(stderr). The file descriptor6indicates this is likely an additional file or socket that has been opened by the process."\\f\\0\\0\\0\\17NJs(8K23&ndhIuY": This is the data that was read from the file descriptor. It's displayed as a string, but non-printable characters are shown using escape sequences. Here's a breakdown of the beginning part of this data:

\\f: form feed (new page) character\\0\\0\\0: three null bytes\\17: an octal representation, equivalent to decimal 15 in ASCIINJs(8K23&ndhIuY: printable ASCII characters

20: This number inside thereadsystem call's parentheses is the maximum number of bytes the process requested to read.= 20: This is the return value of thereadsystem call. It indicates that 20 bytes were successfully read from the file descriptor. If the value had been1, it would indicate an error occurred during the read.

So judging from this it should be safe to assume that the string 'read(6,' is going to be constant and we can leverage this grep on this indicator.

We can see both our username and password above.

The easiest way to obtain the password is to simply grep for the username. With that said there are ways to pull both the username and password from the output with some magic grepping and sed’ing.